[Ep 0] Business Lessons from Childhood

![[Ep 0] Business Lessons from Childhood](/content/images/size/w1920/2024/12/richie-rich.jpg)

The Ones That Don’t Count

The earliest “business” I can remember founding was one in 3rd grade. I taped the crispest $1 dollar bill I could find to a black spiral notebook and called it The One Dollar Club. Every kid paid 25 cents to get in. At lunch, the club funds would go towards buying snacks from the cafeteria lunch lady to share. 4 kids joined and we shared a bag of Garden Salsa Sun Chips. The next day, the dollar was removed from the notebook to pay for a bag of Cool Ranch Doritos. The club quickly shut down after that.

In 6th grade, I recorded a middle school fight on a Nokia 5300 (it’s the same one the monkey director in the Thnks fr th Mmrs music video uses) thinking I could sell viewing access as a school exclusive.

It only risked me getting beaten up by the same kids I taped. Deleted, no thanks.

Willingness to Play

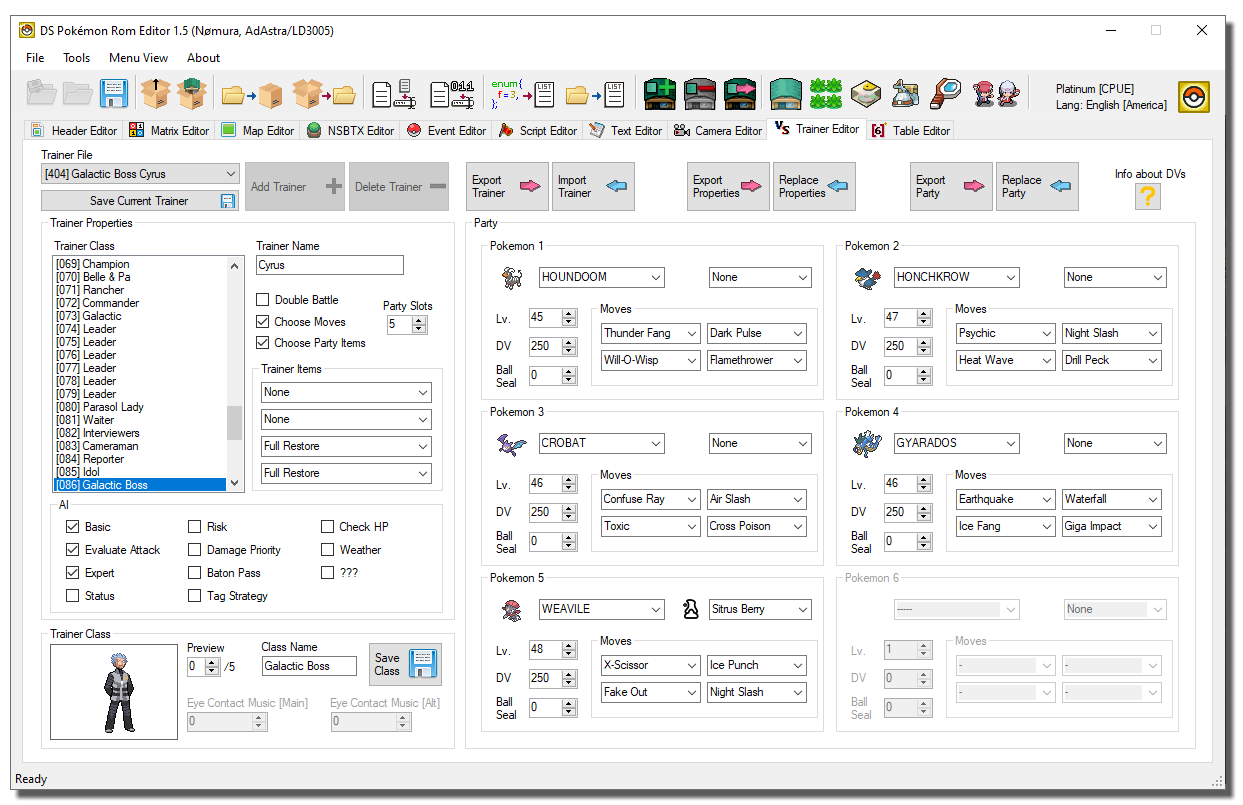

It really started with Pokemon Diamond and Pearl. As my friends and I got into the competitive battle scene (amateur highschool leagues, not official competition), correctly “trained” Pokemon was critical to building a winning team. However, catching, breeding, and then training each of your six digital battle buddies was a grueling and repetitive task. Each one needed the right move sets and perfect IVs/EVs (and you could forget about getting a shiny). Unlike my friends, I had an Action Replay cartridge* which allowed me to hook my game up to my computer and then modify the contents of the save files. Which meant that I could create any Pokemon I wanted. Opportunity.

The first few were free and we tested the hacked Pokemon in combat. I passed around a printed-out Excel sheet during 8th grade math class that allowed people to fill in their orders. Each level of modification was an additional couple of cents. Pokemon that had illegal movesets were extra. Shiny variants were extra. The orders flooded (10 orders).

Each Pokemon averaged around 15 cents, a middle schooler’s average willingness-to-pay for digital goods in 2010. But the lifetime value was there. There were over 300 types of Pokemon and players wanted variants of the same Pokemon.

I would take the order sheet home, click through a cheat program on my computer to give life to my classmates’ requests, and made sure to pack my DS for the next-day delivery during lunch.

I just forgot to consider one important thing. In order to "deliver" the orders to each customer, you had to trade the Pokemon. Except, the game would only let you trade one Pokemon at a time. Customers that put in bulk orders would have to trade with me over and over again. And sometimes my hacked version of the game would crash. By the time I had made my stops, lunch was over and I had made a little more than two quarters.

Information Disadvantage

In 11th grade, I switched from video games to Magic the Gathering. Card games were not new to me; there was a dark period in 9th grade with me blowing my birthday money on Yu-Gi-Oh cards (there’s no business lesson there, that was just an early onset gambling addiction). Magic had a more mature scene and more importantly, a mature secondary market. As new collections released, new game mechanics released. New mechanics meant new strategies. And that meant that cards that were dirt cheap before might shoot up in value.

Every day, I would track the prices of different cards and watch tournaments. I played too, but I was far more interested in theorycrafting the best decks ahead of time as a way to predict the meta (and therefore the market). Rarely was I right. In fact, there was only a singular time.

A new set had released and I thought a certain card (Nightveil Specter) was really cool. I mean, even the name was badass. The general consensus was that the card was not very good and therefore the market priced it at ~4-5 dollars. And so I bought as many as the card shop had, all five of them and placed them all in my card collectors binder to look at.

A month later, a tournament happened and Nightveil Specter is in the winning deck. My friends look at me as if I was omnipotent. The prices had shot up the $25 or more. My first 400% return. I sold four of them and kept one for the memento. Obviously, we had to grow the stack.

Opening a brand new pack of cards has a way of lighting up your neurons in the same way slot machines do. The crinkle of the packaging. The silent drumroll leading up to the chance of a lucrative and rare card. The excitement of hitting a card worth more than the pack cost itself. Cardboard crack.

As I relapsed, I found myself unable to find the next big win. The market was directly influenced by the top players who were winning. But metas were only shaken up when a new set of cards was released so volatility was scheduled, yet abrupt. Or the prices were influenced by cards that went on or off the ban list. I imagine: if you partook in the higher level competitive scene and traveled to the tournaments, you would be privy to better information about which cards were good. Highschool speculation couldn’t compete. 3 months later, when the new set was released, I gave up.

Figuring It Out

Failure never discouraged me from chasing the next hyperfixation. Probably because pure financial gain was never the goal. It was just fun to take part in a subculture in that way. Senior year’s venture caught me by surprise.

A teacher pulled me into her office and asked if I wanted to help an alumni of the highschool with her computer. “You’re good with computers, right?” Of course I was. I was one of the cool kids that knew how to get the VCR working when the teacher was going to play a movie (or in 2014, the VCR was swapped with a SmartBoard).

After school ended, I went over to help my new client set up her new laptop. As Windows was booting up for the first time, I learned that she was previously a courtroom artist. She was incredibly kind and took notes as I showed her how to use the new version of Windows. How to make a folder, how to get onto the Internet, how to install new books onto her PDF reader. By the end, 2 hours had gone by. She gave me $40 ($15 per hour plus a tip) and we scheduled a follow up appointment for the week after for another computer lesson.

I tried processing what had happened on the hour and a half train ride home. I had never been paid so much money for just knowing how to do something. And also, no one had ever seen me as the expert. It was one of the first times I felt undeniably proud.

I started to meet with her semi-regularly. Was it worth the train ride to her apartment and then back home? Not really. But the feeling of getting paid for providing good service was incredible (and the tips helped). She started to ask if I knew how to do other technical things so she could recommend me to her friends. Those friends would then recommend me to more friends.

Soon, I began making house calls across Manhattan three or four times a week after school. My clients were almost all artists. Folks who had written famous screenplays or had giant sculptures out on the streets of New York. Decorated Soho lofts and Midtown condos. It became my thing: Concierge IT for Artists (I was watching Royal Pains at the time and had just learned the word concierge). I even had the narcissistic thought to make a personal business card to leave behind.

As the school year went on, the requests grew from “Can you help me update my LinkedIn?” to “Help, my Gmail got hacked!” I just kept saying yes and trusting that I’d figure it out. Memorably, Google still had a phone support line at the time and I was able to actually recover that Gmail account. Seems impossible nowadays.

My courtroom artist client then asked if I knew how to build a website. Of course, I did. And for $300, I learned how to hack it together on Squarespace. That website is still up today, I just checked. Honestly, solid work.

Eventually, I left New York City for college in Rochester. I passed on my client list to a friend and said my goodbyes. He didn’t really keep it running, but the idea of getting paid for building a website stuck with me.